Ears lock on to the tortured howl long before eyes locate its origins. The staccato bursts of concentrated evil drift down the main straight at Ferrari’s Fiorano test track, the sound of 12 angry pistons and an expensive box of screaming straight-cut gears.

Then – finally – the blood-red missile spears into view. A cool £1 million-worth of F50 GT replete with a full six foot of rear wing rolls up at the workshop next to the latest iteration of the front-engined 575 we are here to drive. The door opens to reveal the legendary test driver Dario Benuzzi.

Just 20 yards away stands last year’s F1 car, a riot of bulges, swoops and creases that no amount of television coverage can do justice to; beyond us lies the giant silver slug that is Ferrari’s F1 base.

With so much going on, clearly just breathing the air at Fiorano is a magical experience, not least due to the clumps of mint sprouting through the grass at our feet, battling to make their presence felt in air that is heavy with the scent of clutch and brake abuse following Benuzzi’s balletic dance around the three-decade-old circuit.

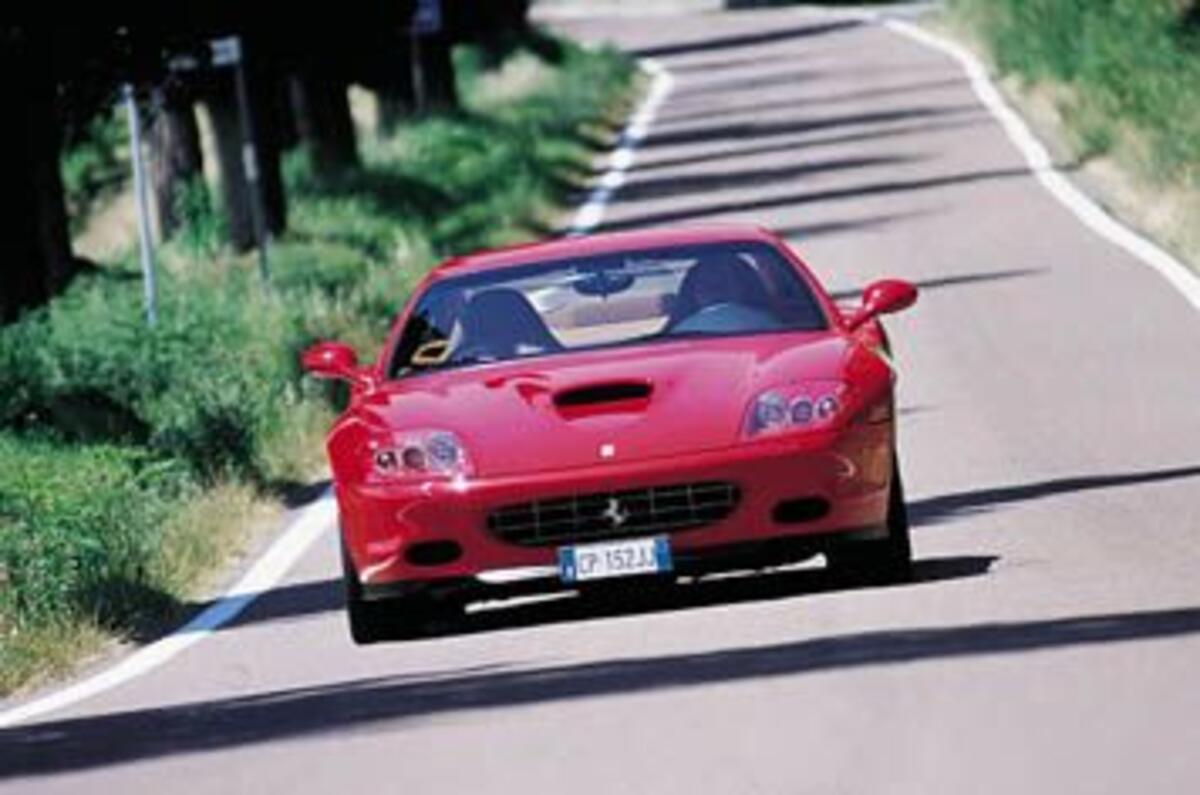

But we’re here to partake, not merely spectate, and with the F50 wrapped up in cotton wool once more, the track is ours. We nose the 575 out onto the Tarmac. Two years ago those words would likely have been the prelude to an enormous disappointment, because someone, somewhere, got their sums wrong.

Evolving the 550M, arguably one of the best-handling front-engined cars on earth, should have presented Ferrari with an open goal. Yet, against all odds, it managed to punt over the bar from six yards.

Prone to thunking its nose at the merest hint of an undulation and with a back end so soft that I almost swallowed the leather off the seat base when I turned into my first fast right-hander at Goodwood two years ago, it suffered the ignominy of taking second-to-last place at our Best Handling Cars contest that year. This proved beyond doubt that heritage is no guarantee of excellence.

The subsequent suspension tweaks of the later Fiorano pack – a £2215 option for UK cars – did much to assuage our initial criticism, but with track days becoming yet more popular, Ferrari felt it was time to turn up the wick one more time.

Ferrari 575M With Handling GTC Pack ranks as one of the least sexy monikers ever attached to a car wearing the Prancing Horse, but it signals a 575 that goes, stops and steers like no other, bar the fully bewinged 575 GTC racers.

At £16,450 on top of the price of a standard 575 (£154,350) you’re looking at roughly eight times the price of the Fiorano kit, but bear in mind that half of that figure is accounted for by colossal carbon-ceramic brakes which we’ve seen bolted to Enzo and Challenge Stradale hubs before but are here on a front-engined Ferrari for the first time.

Boosted to 398mm compared with 330mm for the standard cast iron equivalents, the front discs are clasped by six-pot callipers. The rears grow 50mm to 360mm. All the usual claims are made: big reductions in noise, thermal deformation, fade and wear rate – reckon on 300 hot laps of Fiorano – making them ideal for the sort of track-day and heavy road work the GTC is designed for.

Add your comment